回家的路,不在地圖上,而在心裡。

「沒有住址的家」,不是一種缺席。它不是國家編號下的產權單位,也不只是地圖上的一個定位座標;它是一種仍在進行中的狀態,是在不斷失落與被召喚之間,尋找歸屬的過程;它是一種漂流中的可能性,一種正在生成的家。

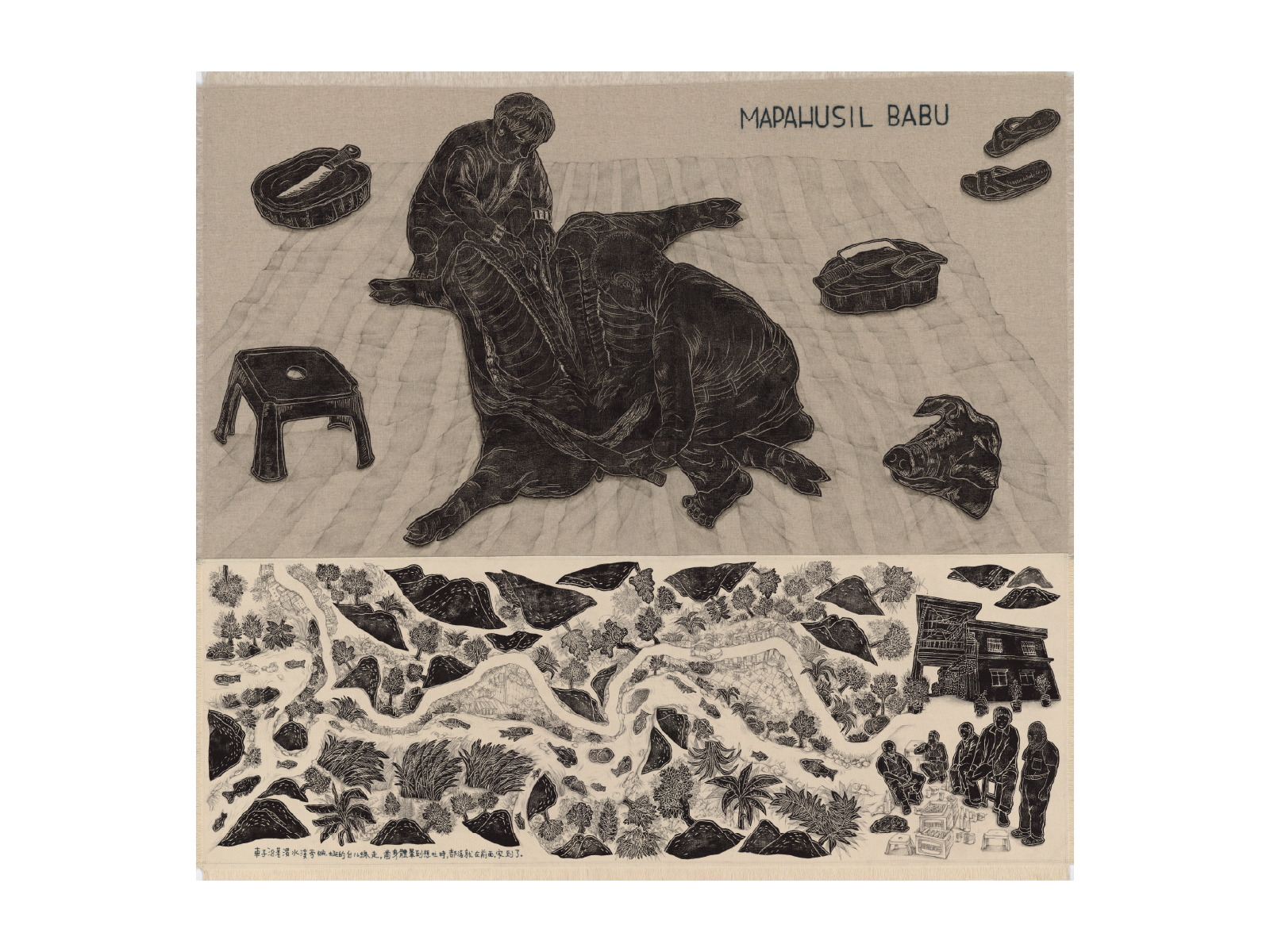

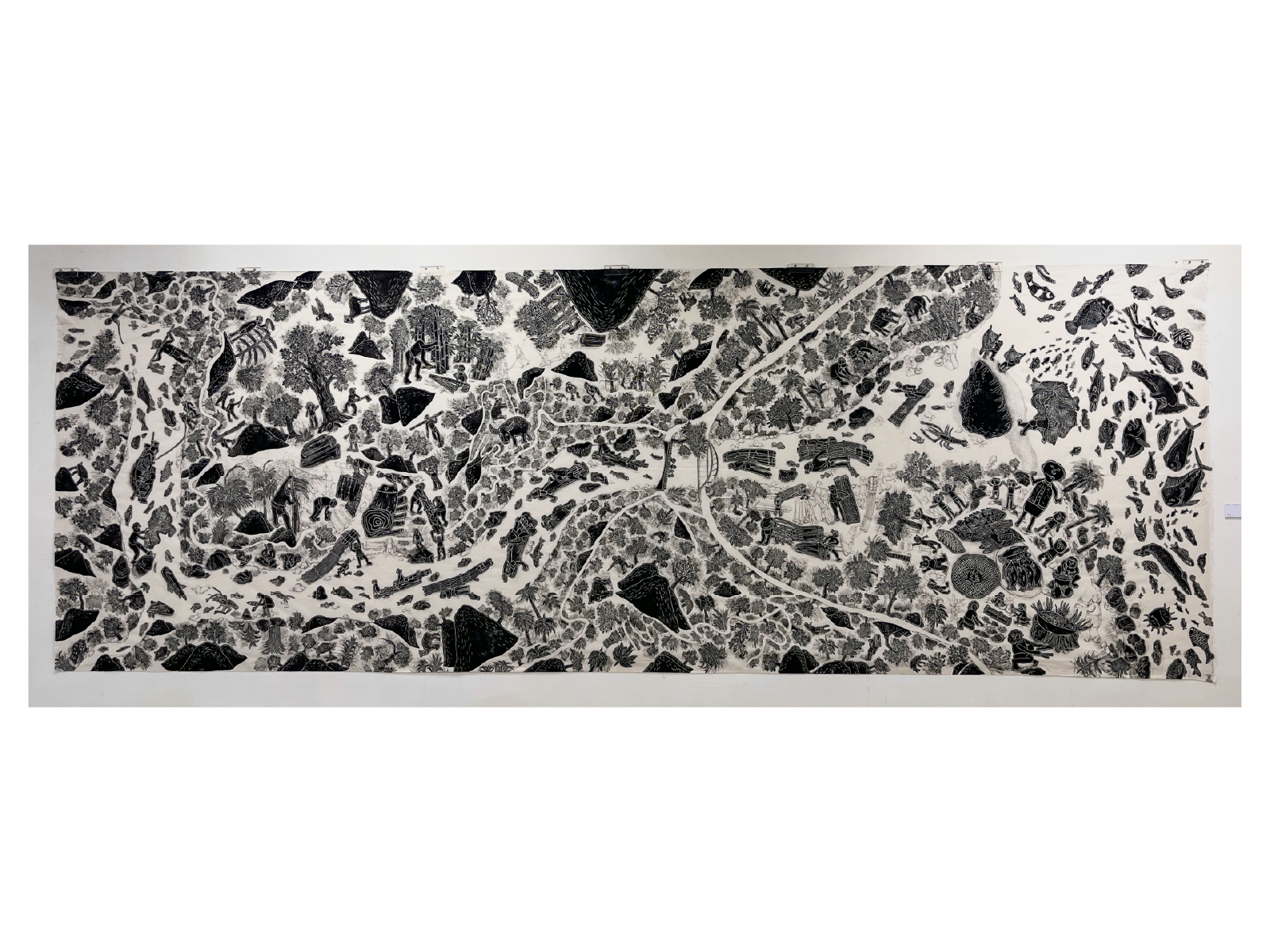

對原住民族而言,遷徙、殖民與都市化不僅帶走了可見的空間與住所,也切斷了語言、信仰與日常生活中的文化實踐。土地不是靜止不動的地點,它承載著祖先的聲音、植物的氣味、河流的方向,以及名字的延續。當土地被劃分、人們被遷移,那些無形的返家路徑也在時間的荒煙蔓草中逐漸斷裂。

我記得在屏東大社部落,有位老人家對我說:「山上的風是香的,工寮在山上的大樹旁,清晨,風吹進工寮,小鳥啾啾叫聲叫醒他。」他說的時候,我彷彿跟著他的記憶回到他山上的家,一個仍活在心裡的地方。

對於居住在城市中的非原住民而言,「家」也可能是一個已被拆除的老宅、一段不斷搬遷的童年、一塊記憶中美好的蛋糕、一條放學回家的巷弄,或者是從未被認同的出身。在國家與社會快速現代化的進程中,家的輪廓變得越來越模糊。越來越多人經歷著一種難以清楚指認的歸屬狀態。

住在社會住宅的阿惠阿姨曾悄悄告訴我她身體的病痛。我不知道她的過去,但我知道,她正在這裡慢慢地落腳、慢慢地安家。

在這樣的時代裡,「家」不再是一個既定的位置。它是一種生成的狀態,一段在行走中被建構的關係。回家的路,無法完全在地圖上尋得;它未必筆直,也未必有名字。但它存在於身體的記憶裡、在講述與被聆聽之間、在每一段生命故事的縫隙中,靜靜顯影。

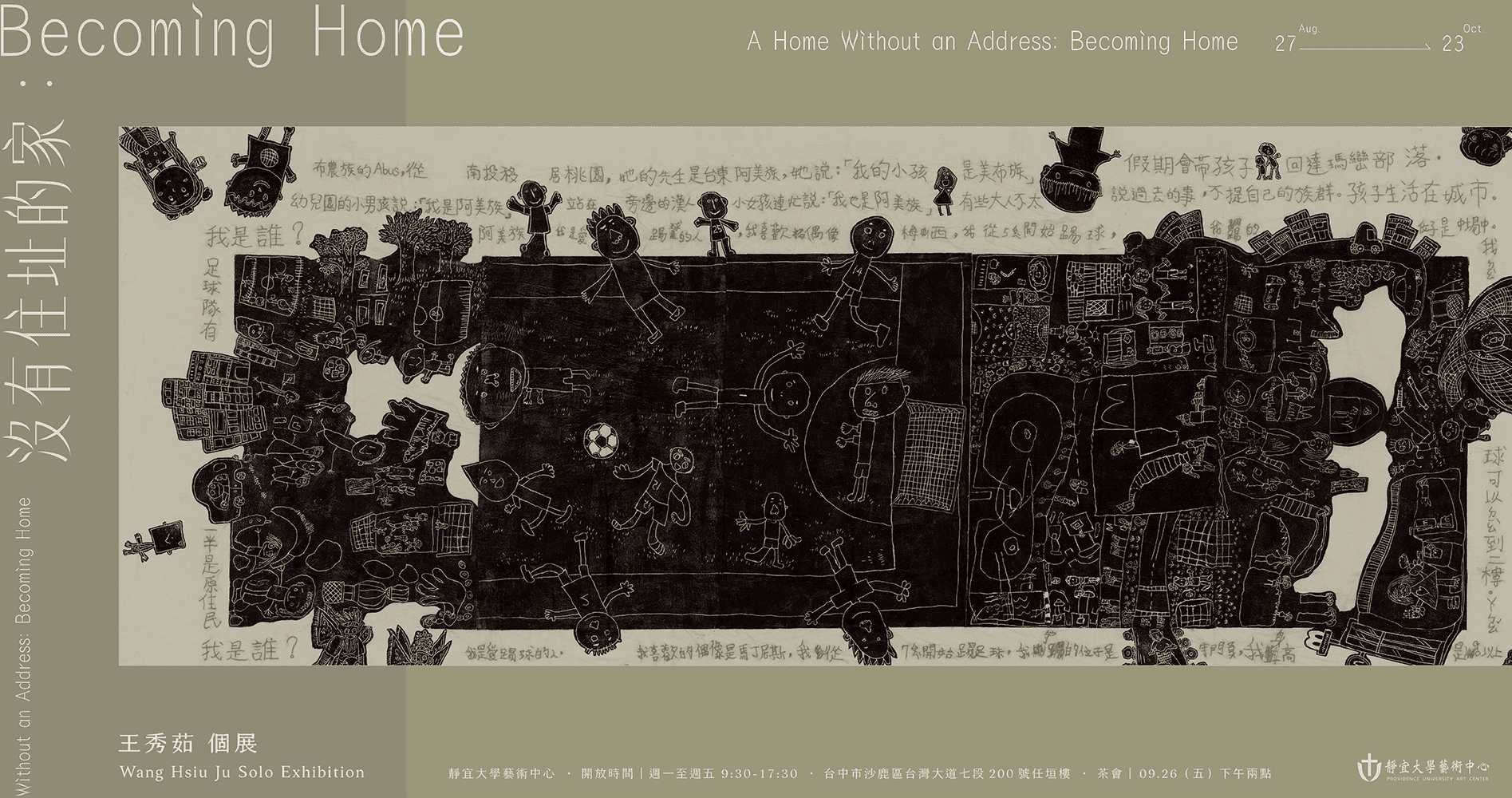

A Home Without an Address: Becoming Home

A “home without an address” is not an absence. It is not a property registered under a national code, nor a fixed coordinate on a map. It is a state still in progress — a process of seeking belonging between loss and calling, a possibility adrift, a home still becoming.

For Indigenous peoples, migration, colonization, and urbanization have not only taken away visible space and shelter, but have also fractured languages, beliefs, and the cultural practices of daily life. Land is not a static place; it carries the voices of ancestors, the scent of plants, the direction of rivers, and the continuity of names. When the land is divided and people are displaced, those invisible paths home begin to unravel, slowly dissolving into the overgrowth of time.

I remember an elder in the Paridrayan tribe of Pingtung once told me:

“The wind in the mountains smelled sweet. The shed was built next to a big tree. Every morning, the wind would blow in, and the birds would chirp and wake him up.”

As he spoke, I felt myself carried by his memory back to the mountain home he once knew — a place still alive in his heart.